Жодугарлар даври: Шотландия ва Европани қамраб олган қўрқув тўлқини

Бу қизиқ

−

22 Октябрь 2025 8790 6 дақиқа

“Мерлин”, “Изтопар”, “Жодугар овчилари”, “Сўнгги жодугар овчиси” каби кино ва сериаллар ўзбек томошабинларига яхши таниш ва ҳатто севимлисига айланган. Лекин бу фильмларга асос бўлган ғоя реал ҳаётда ҳам қачонлардир рўй бергани ҳақида ўйлаб кўрганмисиз? Ҳа, мазкур фильмлар учун ғоя туғилишига сабаб бўлган воқеалар реалликда ростдан мавжуд эди: мазкур фильмлар жодугарлардан қўрқув, уларга қарши кураш ва улар ҳақидаги афсоналар асосида сюжетлаштирилган.

1590 йилларда Шотландия Қироли Жеймс VI нинг жодугарликдан қўрқуви турли ваҳималар қўзғата бошлади, оқибатда минглаб одамлар қийноққа солиниб, ўлдирилди. 1500 йилларнинг охирида шотландияликлар жин (шайтон) мамлакатда мавжуд эканига ишонар эди. Маҳаллий аҳоли уларнинг бўронлар чақириш, чорваларни ўлдириш ва ўлимга олиб келувчи касалликларни тарқатиш қобилияти ҳақида гапирар эди. Одамлар шайтоннинг инсоният жамиятини ичкаридан емириб ташлашга уриниши ва ўз буйруғини бажарадиган махфий агентларни ёллашига ишонарди. Бу агентлар жодугарлар эди ва ҳокимият уларни қироллик манфаатлари йўлида йўқ қилиш зарур, деб ҳисобларди.

Шотландия жодугарлик васвасасига тушиб қолган ягона мамлакат эмасди: ўша пайтда Европада “жодугарлар шайтонга сиғинади” деган, ғоя кенг тарқалиб, жодугар овлари кўпайганди. Диний ислоҳот даврида ҳукмдорлар ўзларининг диндорлигини исботлашни истар эди. Улар буни нопоклик ва ёвузликни тарғиб қилувчи жодугарларни йўқ қилиш билан кўрсатишга ҳаракат қилган.

Сон жиҳатидан Шотландиядаги жодугар овлари жуда оғир кечган. 1590 йилдан 1662 йилгача 5 та кучли ваҳима тўлқини юз берган ва тахминан бир миллион аҳолига эга мамлакатда, асосан, аёллардан иборат тахминан 2 500 киши жодугарликда айбланиб қатл этилган. Бу Европанинг бошқа ҳудудларида қатл этилган жодугарлар сонидан беш баравар юқори. Шотландиянинг жодугарлик ҳақидаги ваҳимага мойиллиги асосан, бир шахс – Қирол Жеймс VI билан боғлиқ эди. У Англия қироличаси Елизавета I вориссиз вафот этганидан сўнг, қариндошлик туфайли 1603 йилда Англия қиролига айланган ва Жеймс I деб атала бошланган.

Қиролнинг китоби

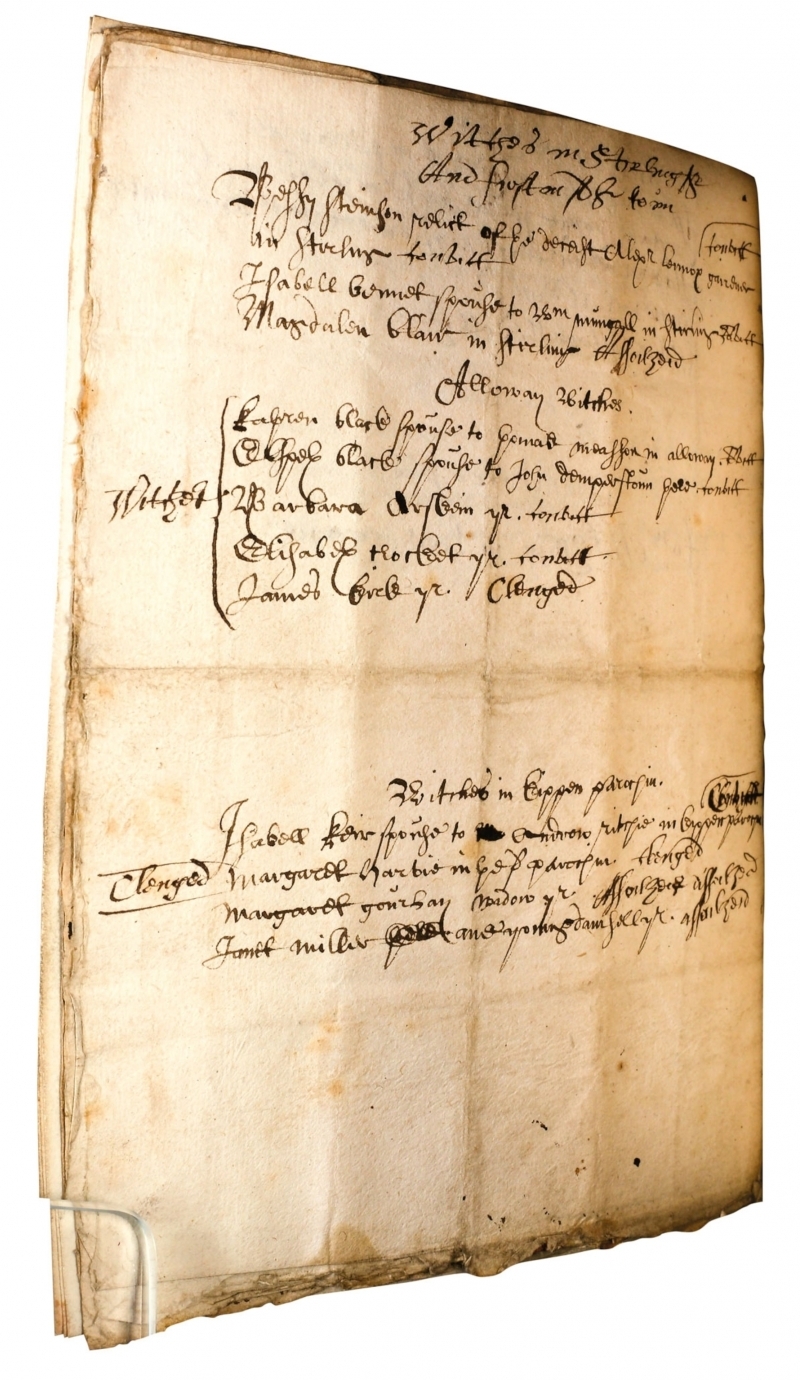

Шотландия парламенти 1563 йилда, Жеймс туғилишидан ҳам олдин жодугарлик билан шуғулланганлик учун ўлим жазоси белгиланган қонунни қабул қилган. Орадан 30 йил ўтиб эса дастлабки йирик ваҳима тўлқини бошланди: ўшанда Қирол Жеймс ўзи ва даниялик келини Анна денгиздаги саёҳати давомида бўронга дуч келиб, бу иш ортида жодугарлар турганига ишонганди.

Гейлис Дункан исмли аёл энг биринчилардан бўлиб айбланди. 1590 йил охирида у хўжайини Девид Сетон томонидан қийноққа солинган ва “бир неча шериклари” исмини айтишга мажбурланган. Кейинчалик Дункан ўз иқроридан воз кечди, аммо бунга қадар ваҳима аллақачон кенг тарқалган эди. 1591 йилда Қирол Жеймс жодугарликда айбланаётган Агнес Сэмпсон исмли аёлнинг даҳшатли иқроридан сўнг жодугарлар устидан суд жараёнларини бошлаб юборди. Аёлга кўра, 1590 йилнинг Хэллоуин кечасида жами 200 нафар жодугар қирғоқдаги Норт-Бервик шаҳарчасидаги черковда йиғилган. У ерда шайтон ваъз қилган ва қиролни йўқ қилишни режалаштиришга ундаган. Бу кўрсатмалар қийноқлар остида олинганига қарамай, қирол ва унинг маслаҳатчилари жодугарлар фитнаси қирол ҳукмронлигига таҳдид солмоқда, деган фикрга келди. Дункан ва Сэмпсон дастлабки тўлқинда ўлдирилган кўплаб айбланувчилардан икки нафари эди, холос.

Олти йил ўтгач, яна бир ваҳима тўлқини юз берди: жодугарлар яна шахсан Қирол Жеймсга қарши фитна уюштираётгани ҳақида хабарлар тарқалди. “Балверининг буюк жодугари” деб аталган Маргарет Аткин исмли аёл бошқа жодугарларни аниқлай оладиган қудратга эга эканини даъво қилди ва унинг сўзига асосланиб, кўплаб одамлар ўлимга ҳукм қилинди. Ушбу тўлқин Аткиннинг сохта экани фош этилгач, тўхтади. Бу воқеа жодугар овчиларини ниҳоятда шармандаликда қолдирди ва ўша йили Қирол Жеймс ўзининг қилмишларини қисман оқлаш мақсадида “Демонология” номли рисоласини чоп эттирди.

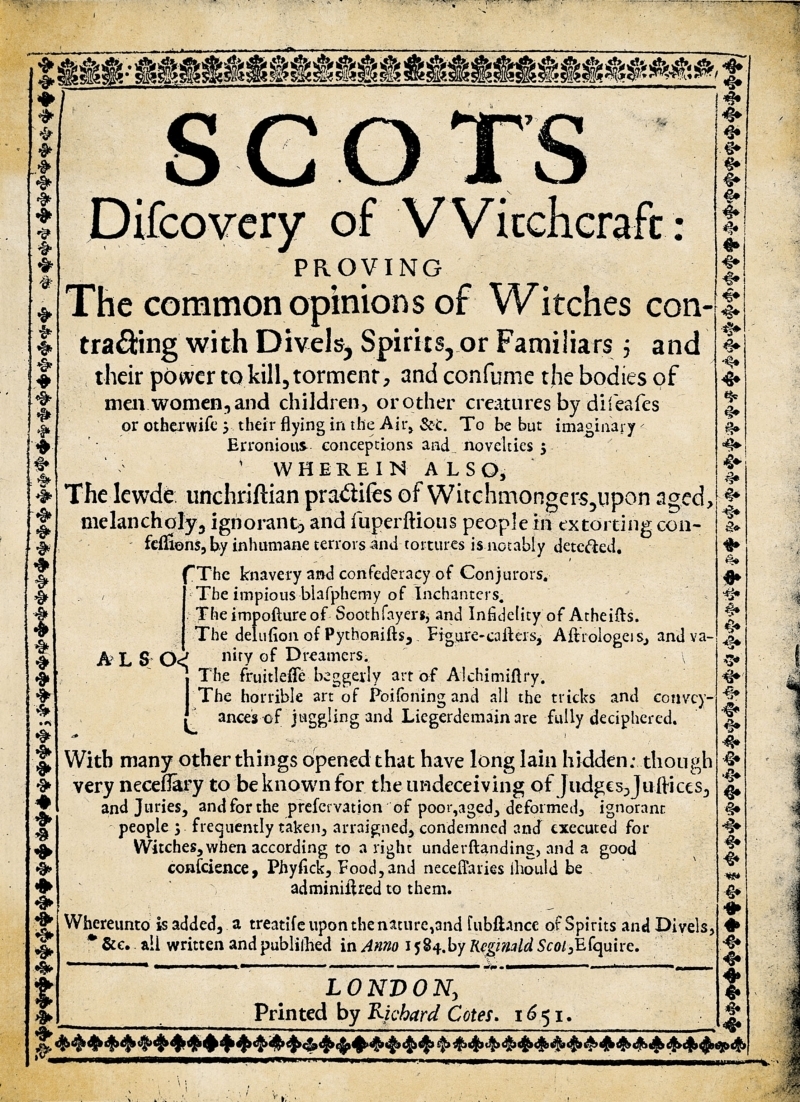

XVI асрда жодугарлик илмий қизиқиш уйғотган мавзу эди ва қиролнинг бу китоби у ўзини зиёли инсон сифатида кўрганини билдиради. “Демонология” шайтон дунёда қандай фаолият юритишини тушунтиради. Жеймснинг китобига кўра, жодугарлик – одамлар ва жинлар ўртасидаги махфий фитна бўлиб, улар қўлларидан келганича ёвузлик қилишга уринади.

Жеймс Англия тахтига ўтиргач, у янги диний душман – жанговар католиклар билан тўқнаш келди. 1605 йилда католикларнинг парламентни портлатиб, қиролни ўлдиришга қилган ҳаракатидан сўнг, Жеймс жодугар овларидан воз кечиб, эътиборини сиёсий фитналарни йўқ қилишга қаратди. Қирол Жеймснинг диққат маркази ўзгарганига қарамай, жодугарлик ҳақидаги ғоялар Шотландия жамиятига сингиб кетганди: жодугар овлари нафақат миллий, балки маҳаллий масалага айланди. Жодугарларни йўқ қилиш учун амалий чоралар асосан шотланд жамиятининг маҳаллий етакчилари томонидан амалга оширилган.

Айбланувчилар

“Катта ёшли жанжалкаш аёл”лар жодугарликда энг кўп айбланган тоифа эди. Дастлабки гумонланувчилар қўшнилари томонидан сеҳр ишлатганликда айбланган шахслар бўлган. Бора-бора гумондор аёллар шайтон билан битим тузишда айбланди. Бу одатда “шайтон билан жинсий муносабат”ни англатган. Эркакларга қўйилган кам сонли айбловларда эса жинсий элемент тилга олинмаган. Эркак киши жодугарликда айбланиши учун жуда ноодатий иш қилган бўлиши керак эди. Натижада, ҳукм қилинган жодугарларнинг 85 фоизи аёллар бўлган.

Қийноқ орқали олинган иқрорлар

Жодугар овчилари “далиллар”ни қийноқ орқали қўлга киритган. Айбланувчилардан “ҳамкорлари” исмларини айтиш талаб этилган ва номи тилга олинган одамлар ҳибсга олиниб, шайтон билан битим тузганликларини тан олишга мажбур қилинган.

Баъзи кўрсатмалар фантастик унсурларни ўз ичига олиб, ғайриоддий ва хаёлий уйдурмалар ҳақида ҳикоя қилган. Масалан, 1644 йилда “Маргарет Уотсон иши” қуйидаги ҳайратланарли тафсилотларни ўз ичига олган эди:

“Сен тан олдингки ... сен ва бошқа жодугарлар ўликлар жасадларини қазиб олиб, уларнинг аъзоларидан ўз шайтоний ниятларингизни амалга ошириш учун фойдалангансиз, йиғинларда Худонинг номини ҳақорат қилгансиз, ичимлик ичиб, рақсга тушгансиз, Молли Паттерсон мушук устида учган, Жанет Локкай хўроз устида учган, Маргарет Уотсон бойчечак дарахтида учган, ўзинг эса сомон дастасида учгансан, Жан Лаклан эса кекса дарахтда учган”.

Энг кенг тарқалган қийноқ тури уйқусизлик орқали қийнаш эди. Тахминан уч кун ухламасликдан сўнг, гумонланувчи нафақат сўроқчиларга қаршилик кўрсатиш қобилиятини йўқотар, балки галлюцинацияни ҳам бошдан кечирар эди. Натижада улар хўроз устида учиш каби ғайриоддий тафсилотларга тўла кўрсатмалар беришган.

Европанинг аксарият давлатлари сингари Шотландияда ҳам жодугарлар ёқиб ўлдирилган.

Ваҳима тўлқинларининг сўниши

XVII аср охирларига келиб, аста-секин диний хилма-хиллик қабул қилина бошлади. Янги илмий ғоялар жодугарлик ҳақидаги қатъий диний эътиқодларни заифлаштирди. Судлар энди қийноқ остида олинган кўрсатмаларни далил сифатида қабул қилмай қўйди. Натижада, жодугар овлари давлат учун муҳим масала бўлмай қолди ва 1662 йилдан кейин Шотландияда ҳеч қандай миллий миқёсдаги тўлқин қайд этилмади.

Шунга қарамай, маҳаллий аҳоли орасида жодугарлардан қўрқув ярим асрча давом этди. Энг охирги расмий қатл 1727 йилда Дорнохда амалга оширилган. Ниҳоят, 1736 йилда Британия парламенти 1563 йилги жодугарлик тўғрисидаги қонунни бекор қилди.

Шундан сўнг, Шотландияда ваҳима тўлқинлари қурбонлари хотирасига бир нечта кичик ёдгорликлар ўрнатилган, аммо ҳанузгача катта, расмий ёдгорлик барпо этиш ҳақида чақириқлар мавжуд. Бу орқали 4 аср аввал қийнаб, азоблаб, ўлдирилган минглаб бегуноҳ аёл ва эркакларга нисбатан содир этилган буюк адолатсизлик расман тан олиниши кераклиги айтилади.

Live

Барчаси