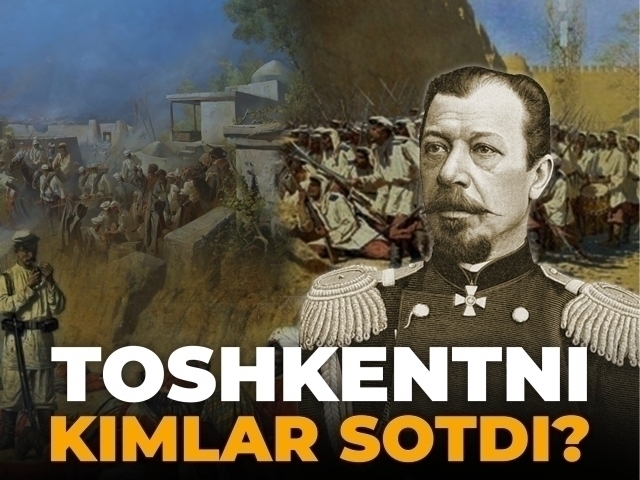

Secrets behind the capture of Tashkent: Who sold the city?

Review

−

02 July 2025 45594 8 minutes

On June 29, marking the 160th anniversary of the capture of Tashkent by Russian forces under General Mikhail Grigorievich Chernyayev, scholars from the Institute of History at the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan held a scientific conference titled “160th Anniversary of the Capture of Tashkent: Truth and Fiction.” As is known, the Russian troops began their campaign to seize Tashkent—one of the key military-political and economic centers of Turkestan—on October 1, 1864, and succeeded on June 29, 1865. At the meeting, Academician Azamat Ziyo emphasized that the topic holds not only historical but also political significance. He stressed that the invasion and resistance must be studied not merely as historical events, but also from the perspective of the true nature of colonial aggression and the people’s yearning for freedom. He also highlighted the need to expose various “scientific-theoretical” distortions aimed at justifying the Russian Empire’s incursion into Turkestan.

The capture of the city laid critical groundwork for the subsequent conquest of the Uzbek khanates. The loss of Tashkent was not merely inevitable due to the military imbalance but was also the result of certain individuals prioritizing personal gain over patriotism. So, what was the situation in the skies over Tashkent 160 years ago? What is known about the deceitful tactics of the Russian invaders and the local collaborators who aided them?

“We brought Russian captains and soldiers and handed over the city to them…”

According to historical analysis, instability that began in the early 16th century—following the crisis of the Timurid Empire—led Turkestan to fall behind many parts of the world by the 18th and 19th centuries. After subduing the Kazakh zhuzes, Russian forces turned their attention to the Uzbek khanates, targeting Tashkent first. At the time, Tashkent was a major hub for politics, economics, administration, and trade within the Kokand Khanate.

The first assault on the city, which was protected by thick walls and 12 gates, took place in autumn 1864. However, due to the fierce resistance by its residents, Chernyayev failed to take the city. Renewing the campaign in April 1865, the Russian forces finally captured Tashkent on June 17. Afterward, the ceremonial golden keys to the city’s 12 gates were handed over to Chernyayev, marking the establishment of Tsarist Russian rule in Tashkent and its surrounding territories.

General Mikhail Grigorievich Chernyayev

General Chernyayev later drafted a document claiming that Tashkent had voluntarily joined the Russian Empire, coercing several city officials into confirming it. Those who viewed this falsehood as an act of betrayal were exiled to Siberia. The document was intended to justify Russia's actions in the eyes of rival powers such as Great Britain and the international community.

According to the Tashkent Encyclopedia published in 2009, the document included the sentence: “...for the peace of the citizens and the country, we brought Russian captains and soldiers with our full will and encouragement and handed over the city to them.” However, historian Muhammad Salihkhodja wrote that when the fabricated content was exposed, a city official named Domla Muhammad Salihbek Akhund refused to approve it, saying:

“We will state without concealing the facts and events that the cities and fortresses from Tashkent to Akmasjid and from there to Fulja encountered the same fate. The Russian soldiers captured these places through warfare and plunder. The war came swiftly, without warning or negotiation. Tashkent was besieged without water or food for 42 days, from mid-Zulhijjah until the 12th of Safar. After the martyrdom of the commander-in-chief, Mullo Alimqul, the city was left leaderless.

The people of Bukhara, Khorezm, and Fergana offered no assistance. The citizens of Tashkent held firm to defend their homeland and faith, continuing the fight. After midnight on Tuesday, near dawn, Russian troops stormed the Alley Gate and scaled the fortress wall while most were asleep. The battle resumed and lasted two more days and nights until Thursday. During that time, many buildings, shops, and homes were set ablaze, and the people endured intense hunger, thirst, and hardship. Eventually, a peace treaty was signed.”

Angered by this defiance, Chernyayev exiled Muhammad Salihbek and his supporters, including Hakimboy, Berdiboy, Azimboy, Mulla Mirzaa’lam Akhund, Mulla Muzaffarkhodja, and Mulla Fayzinor Domla.

Other city officials, under similar pressure, complied with the demands and helped draft the treaty with the language Chernyayev required.

Sotmaydi yurtini biror otboqar (No horse breeder would sell his land)

Sotsa, zerikkandan ziyoli sotar... (If he did, it was out of desperation...)

How true are the lines from Muhammad Yusuf’s poem Ajab—this becomes evident in the example of betrayals committed against Tashkent. According to historian Hamid Ziyoyev in his book History of the Struggles for the Independence of Uzbekistan, during the capture of Tashkent, a “helping hand” was extended to the Russian invaders from within the city.

Specifically, after the execution of Boyzokboy, a leader of the Duglat tribe who acted as a spy for Russian forces during their 1864 campaign, his son Okmulla continued the betrayal. He aided General Chernyayev by organizing the transportation of food, weapons, and supplies into Tashkent ahead of its capture.

In November of that year, a spy was apprehended carrying a letter from Abdurakhmonbek Shodmonbekov, one of Tashkent’s officials, addressed to Chernyayev. According to Ziyoyev, the Russian general obtained vital intelligence through such insiders. Eventually, Abdurakhmonbek fled Tashkent to join Chernyayev directly.

Ziyoyev notes that, following Abdurakhmonbek’s advice, Russian forces targeted the Niyozbek fortress near Chirchik to cut off the city's water supply. They also diverted the Kaykovus stream into the Chirchik River by breaking its dam, further weakening Tashkent’s defenses.

Despite this, fierce battles were fought to save the city. Even after Russian forces breached the Kamalon Gate, fighting continued in the neighborhoods and alleyways. However, according to the historian, traitors helped Russian troops locate a munitions depot within the city, which was then destroyed. This sabotage played a decisive role in the collapse of the city's resistance.

The lack of water, food, and ammunition gradually exhausted the population. On June 17, 1865, the people of Tashkent, unable to withstand the siege any longer, were forced to surrender.

Some sources claim that wealthy merchants in Tashkent—motivated by the prospect of trading duty-free within the Russian Empire—provided the invaders with sensitive information about the city’s defenses, security systems, and vulnerabilities.

It is also said that their refusal to submit to either the Kokand Khanate or the Bukhara Emirate led some of these elites to ally with General Chernyayev. Notably, influential figures such as Muhammad Soatboy are believed to have supported him.

In his 1914 book, Collection of Materials on the History of the Conquest of Turkestan. Turkestan Region, Colonel Andrian Serebrennikov writes that a group of local merchants acted as internal allies. He claims they placed their trust in Chernyayev and promised to open the city gates in exchange for the right to trade freely in cities like Moscow and Novgorod.

While not all merchants favored aligning with the Russian Empire, many residents began to believe that remaining under Kokand or joining Bukhara would not serve their interests. As a result, they sought the protection of a stronger, more centralized authority, shaping the city’s fate accordingly.

Serebrennikov also notes that in 1865, one of the city’s wealthiest men, Turakhon Zaybukhanov, traveled to St. Petersburg. There, he appeared before the emperor and proposed the conquest of Tashkent, claiming that 50 influential individuals would support the Russians and even offer 2,000 men to assist them.

People leave, traces remain

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Kokand Khanate, along with other regional khanates, engaged in active caravan trade with China, India, Iran, and others. Beginning in the second decade of the 1800s, trade with Russia also grew substantially. However, the friendship between Russia and Kokand, established in the early 19th century, deteriorated into hostility by mid-century.

When faced with the choice of trading with their homeland or with Russia, many merchants and officials regrettably chose the latter. For them, economic opportunity outweighed the country’s sovereignty. Thus, the fall of Tashkent was not due to military force alone—it was also a consequence of internal betrayal.

Despite the vast power of the Russian Empire and its global influence at the time, there were still those who defended Tashkent to their last breath. Even in defeat, they never bowed, never gave in.

As the saying goes, “Cowardice does not prolong life, courage does not hasten death.” Those who betrayed Tashkent for momentary gain or out of fear, and those who gave their lives for the city, have both passed. But only the names of the brave are remembered with honor, while the names of the traitors remain cursed.

Live

All