Whose hands hold Greenland’s future?

Review

−

17 January 2549 11 minutes

Once, after buying Alaska from the Russian Empire for a negligible sum, the United States is now seeking to gain control of the world’s largest island as well. The White House, advancing a message that can be summed up as “money or force,” is trying to justify its claims to Greenland under various pretexts. NATO and the European Union are in a difficult position: either enter into conflict with a key partner or silently watch core principles be violated.

Who owns Greenland?

A look at today’s political map reveals a striking paradox: Denmark, a small country with a population of under six million, controls the world’s largest island—Greenland. On the Mercator projection, the island appears nearly the size of Africa; in reality it is smaller than it looks, but it is still roughly five times larger than Uzbekistan. At first glance, it seems almost extraordinary that such a strategically important territory—one that influences control over Arctic routes—has autonomous status under a small European state.

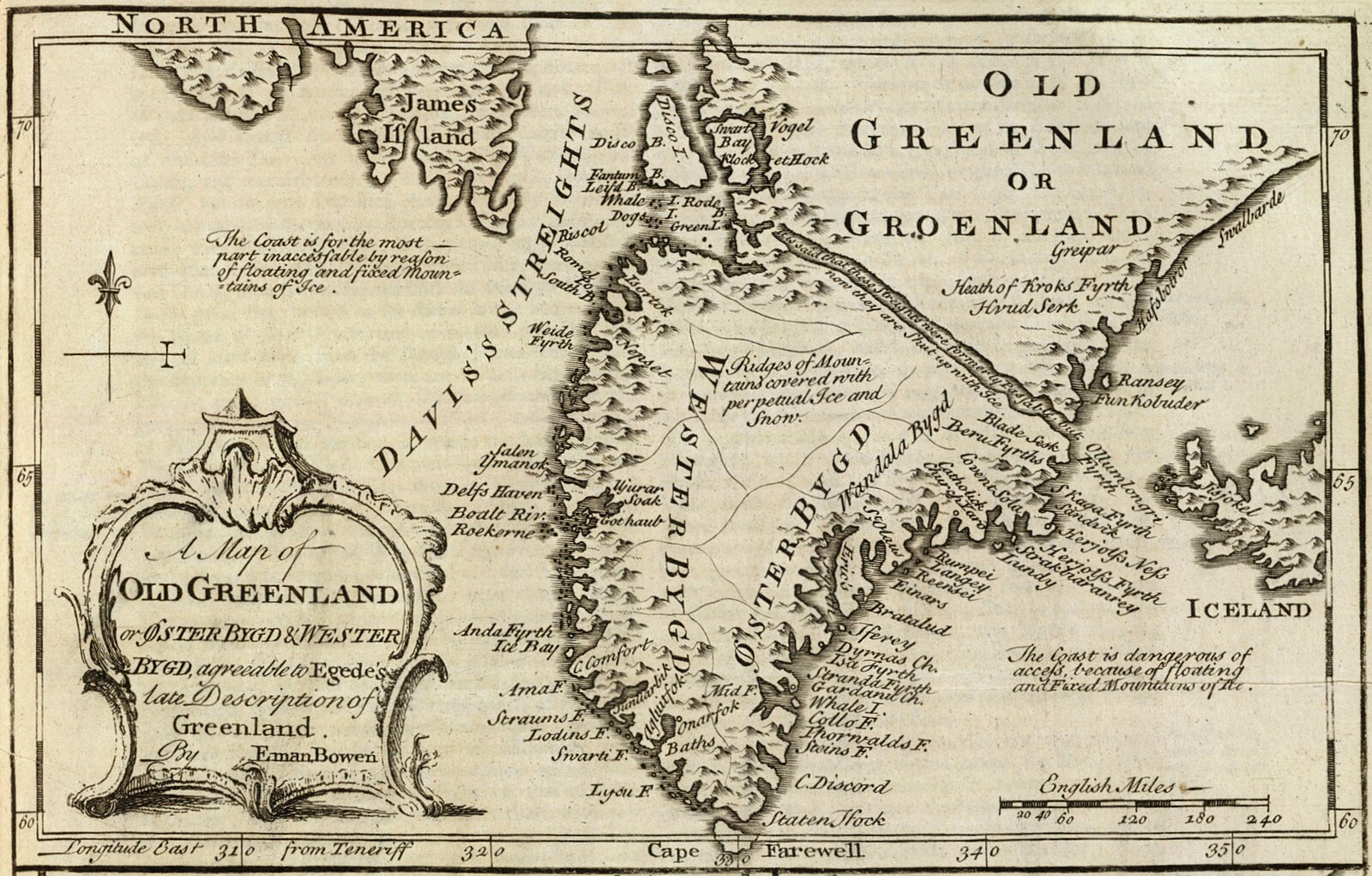

In 982, a Norse explorer known as Erik the Red arrived in Greenland and established the first European settlement. According to common interpretations, he gave the island its current name to attract settlers, calling it “Greenland” (“green land”) to make the new territory sound appealing. The branding worked, and Vikings arrived in hundreds of ships to settle the icy landscape. Initially independent, the territory later agreed, starting in 1261, to pay tribute to the Kingdom of Norway. In 1397, after the formation of the Kalmar Union involving Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, Greenland also came under the rule of the Copenhagen crown, which led the union.

After Denmark’s defeat during the Napoleonic Wars, it was forced to sign the Treaty of Kiel. Under the agreement, Copenhagen ceded Norway to Sweden, while its overseas possessions—Greenland, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands—remained under Danish control.

Although contact with the island was temporarily disrupted between the 15th and 17th centuries, the Danish-Norwegian church continued to treat these lands as part of its ecclesiastical jurisdiction (diocese). In 1931, Norway declared the eastern part of Greenland as its own, triggering a dispute with Denmark. The case was definitively resolved in Denmark’s favor in 1933 by the Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hague.

Greenland’s status as part of Denmark is therefore rooted in a long historical process and reinforced by established international legal norms.

Why Greenland matters to the United States

Historically, U.S. presidents’ interest in Greenland is not new. The idea emerged more than 150 years ago and has repeatedly returned to the agenda under different administrations.

The U.S. purchase of Alaska in 1867 for $7.2 million whetted the appetite of some policymakers in Washington. Among them was then–Secretary of State William Henry Seward, who began to show interest in Greenland and Iceland. Seward promoted a “Northern route” strategy. In his view, the United States should control the northern reaches of North America, including Canada, Alaska, Greenland, and Iceland. The aim was to push the British Empire out of the region and turn the U.S. into a central hub of global trade. At the time, however, the U.S. Congress did not support the idea.

Although Congress rejected Seward’s approach, President Andrew Johnson also became interested in Greenland. An informal purchase proposal sent to the Danish government and a special expedition dispatched to study Greenland’s natural resources contributed to political tensions around his presidency. Ultimately, domestic turmoil, Johnson’s impeachment, and congressional resistance caused the plan to stall.

In U.S. history, President Harry Truman is often regarded as the leader who treated the Greenland issue most seriously. After World War II, the Arctic’s strategic importance in defending against the Soviet Union grew sharply.

In 1946, Truman offered $100 million in gold for Greenland. The talks were conducted in secret. Although Denmark initially rejected the proposal outright, by 1951 it allowed the United States to maintain the Thule military base on the island.

Donald Trump, known for reviving old ideas, also returned Greenland to the political agenda early in his first term. In 2019, reports that Trump wanted to buy Greenland sparked widespread international attention. In an August 18 interview, he argued that Greenland was becoming a burden for Denmark and that the territory was extremely important for the United States. “Conceptually, this is costing Denmark a lot, because they pay close to $700 million in subsidies every year. For the United States, it would be very good strategically,” Trump said.

After these remarks, relations between Denmark and Washington cooled. Danish officials described the idea as “absurd.”

After returning to office for a second term in 2025, Trump did not abandon the concept. On January 4 of the current year, speaking with journalists aboard Air Force One, he again raised the issue of purchasing—or annexing—Greenland.

“Greenland is critical to us from a national security perspective. It’s a very strategic area. There are Russian and Chinese ships all over the place. Greenland is a national security matter. Denmark cannot defend Greenland. Recently they said they strengthened security by adding just one extra dog sled. It’s ridiculous,” Trump told reporters.

Although Danish authorities have continued to reject these claims, Washington keeps invoking strategic defense arguments against China and Russia, while also repeating historical narratives about ownership. Trump’s special envoy for Greenland, Jeff Landry, has even accused Denmark of “taking over” the world’s largest island.

“History matters. During World War II, the United States protected Greenland’s sovereignty when Denmark was not able to do so. After the war, Denmark re-occupied it by bypassing and disregarding UN protocols. This is not about hostility—it should be about hospitality,” Landry said.

If history alone were used as the basis for modern borders, today’s boundaries would have to be rewritten entirely. In the contemporary world, violating international legal norms and relying solely on the past would destabilize global order.

Defending Greenland from Washington

What makes Trump’s approach unusual is its bluntness. Discarding diplomatic language, he is effectively saying: “Sell Greenland to us, or we will take it by force.” His insistence not on leasing arrangements but on full ownership under the banner of security has raised serious alarm in political circles. It reflects one of the most dangerous trends of 21st-century geopolitics: powerful states normalizing claims to other sovereign territories by citing national security.

Washington’s persistent pressure has also strained Denmark’s patience. After Trump’s January 4 interview, Greenland’s Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen issued a sharp statement, calling the annexation idea a “fantasy.”

“There must be no more pressure. No more hints or insinuations. These annexation fantasies must stop. We are ready for dialogue. We are ready for discussions. But this must be done through the right channels and with respect for international law,” the prime minister said.

When a country with the world’s most powerful military makes such demands of Denmark, Copenhagen clearly needs support. As a full member of both NATO and the European Union, Denmark has, in theory, access to collective strength that could allow a meaningful response to the Trump administration. Yet with the United States in the role of aggressor, both organizations have largely remained silent.

In theory, the European Union, with a population of around 450 million, has substantial economic leverage over the United States. It could threaten countermeasures ranging from restricting U.S. military basing in Europe to limiting European purchases of U.S. government debt. In practice, however, a lack of unity among EU states in responding to U.S. pressure, energy dependencies, and the longstanding transfer of defense responsibilities to NATO have prevented the bloc from taking firm, practical action against Trump’s policy.

In an interview with the Financial Times, a number of European officials openly expressed frustration with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte’s silence. They argued that Rutte should be the figure able to speak to Trump on Europe’s behalf and restrain his most aggressive plans. If the sitting U.S. leader advances territorial claims against Greenland—a part of Denmark, a full NATO member—and the alliance remains silent, it would signal that the rules of international relations have changed. European elites fear that if the U.S. openly dismisses international law and NATO tolerates it, a climate of impunity for powerful states will be created.

After growing criticism, social media reports began circulating that NATO and European actors were sending troops toward Greenland. According to these posts, forces from Germany, Sweden, and Norway—operating under the NATO banner—were heading to the island, with personnel expected to arrive between January 15 and 17. The stated aim of the mission is to assess ways to ensure security in the region. Although the number of troops involved is reportedly small, even the start of such actions is viewed as a significant symbolic step from Europe.

Another important aspect of the situation is Greenland’s autonomous status. Although it is formally part of Denmark, the island has the right to self-government. In this context, decisions about Greenland’s future are increasingly being framed as a matter for the local population. Leaders of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, and Denmark issued a joint statement opposing U.S. pressure.

“Greenland belongs to its people. Decisions regarding relations between Denmark and Greenland can only be taken by these two parties,” the statement said.

Five political parties in Greenland’s parliament also released a joint declaration demanding an end to what they described as disrespectful treatment by the United States.

“We do not want to be American, we do not want to be Danish, we want to be Greenlandic,” the statement said.

The politicians stressed that Greenland’s future must be decided only by its citizens and that external interference should not be allowed. They also said Greenland wants to continue cooperation with the United States and other Western countries.

At the same time, Russia’s former president and current deputy chair of the Security Council, Dmitry Medvedev, also weighed in, urging U.S. President Donald Trump to “hurry” on Greenland. He claimed that if Trump delayed, Greenlanders might choose to join Russia.

“Trump should hurry. According to unconfirmed information, a snap referendum could take place in Greenland within days, where all 55,000 residents could vote to join Russia. After that—game over. There will be no new stars on the flag. Russia will gain a new, 90th federal subject,” Medvedev wrote on X.

In reality, Greenland’s population has already signaled its position. At a press conference in Copenhagen, Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen stated that Greenland would choose Denmark.

“Greenland will not belong to the United States. If we are forced here and now to choose between the United States and Denmark, we choose Denmark. We choose NATO. We choose the Kingdom of Denmark. We choose the European Union,” Nielsen said.

At the same press conference, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen also spoke, reiterating that the territory would not be sold.

“Our message is clear: Greenland is not for sale. We have said this from the beginning, and we have told the Americans from the beginning as well: if this is about security, there is a great deal we can do together—and should do together,” she said.

Overall, Trump’s stance on Greenland has not been warmly received even within the United States. After the events in Venezuela, criticism of Trump’s broader policy approach has intensified among both the public and officials, and impeachment discussions have resurfaced repeatedly. For that reason, the risk of Greenland being annexed appears limited. However, regardless of what happens, the situation demands major resolve not only from NATO or the European Union, but from the wider international community. At this moment, the island is not only Denmark’s issue—it is a test for international law itself.