Are Uzbeks being “Afghanized”?

Review

−

07 January 26798 10 minutes

The former Soviet Union’s “divide and rule” policy has always proven effective. Did you know that another Uzbek people live right next to the Uzbeks of Uzbekistan? The Amu Darya River separates us. Centuries of harsh political decisions have driven a wedge between us. These lands are sometimes referred to as Southern Turkestan. On the northern bank of the river live citizens of independent Uzbekistan, while on the southern bank reside Afghan Uzbeks – ethnic kin of the same roots and language.

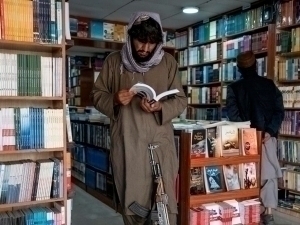

For many years, they have lived separated from one another. Nevertheless, Uzbeks in Afghanistan have managed to preserve their language, culture, and national identity, or as they say in their own tongue, their cultural heritage. Unfortunately, after the Taliban came to power in 2021, attitudes toward Afghan Uzbeks changed sharply, and their lives became even more difficult. QALAMPIR.UZ has received numerous appeals stating that the Taliban is rapidly pursuing a policy aimed at erasing the cultural and historical identity of millions of Uzbeks in Afghanistan and forcibly Pashtunizing them.

Regrettably, Afghan Uzbeks face discrimination on both sides: in Afghanistan, they are marginalized for being Uzbek, while in Uzbekistan they are often pushed aside for being labeled Afghan. If you hear someone speaking pure literary Uzbek in the tradition of Qodiriy or Cholpon on the streets, know that this person is our compatriot, an Uzbek. Many Uzbeks wish to speak openly about their fate, but most remain silent because their family members still live in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, we managed to speak with several of our compatriots on this issue.

According to official data from 2017, more than 3.5 million Uzbeks currently live in Afghanistan, while unofficial sources estimate the number to exceed 10 million. Prominent Uzbek officials, governors, teachers, writers, poets, and ordinary citizens with democratic views who held positions during the republican era have faced repression and exile since 2021. This is not the first nationalist-driven action by the Taliban. Thousands of reports attest to this. Earlier, the Taliban carried out mass dismissals of Uzbeks from the security forces.

According to the United Nations, the order to reduce troop numbers was issued directly by the Taliban leadership. While Kabul officials explained the cuts as a result of a budget crisis, the reductions were carried out mainly in provinces predominantly populated by Uzbeks.

In 2023, the monument to Alisher Navoi, built about 20 years earlier in the city of Mazar-i-Sharif, was vandalized several times by local authorities. Initially, the Taliban attempted to cover up the incident by blaming local residents. Uzbekistan’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Akhror Burkhanov described the incident as vandalism.

“We received with deep regret reports that monuments to our great poet Alisher Navoi were damaged in Afghanistan. Our diplomats contacted Afghan representatives regarding this matter. According to them, this act of vandalism does not reflect the official policy of the interim government, which supports strengthening centuries-old friendly relations with brotherly Uzbekistan. It was the result of irresponsible actions by unknown individuals and harms our shared historical and cultural heritage. Afghan representatives stated that measures would be taken to restore the monuments and show respect for our common legacy,” Burkhanov wrote.

By 2025, it was openly acknowledged that the monument had been completely destroyed. Following strong public outrage in Uzbekistan, the Taliban once again offered an explanation. They claimed that the location of the Navoi monument was unworthy of the great scholar’s memory and that a more impressive complex should be built, which is why the monument was removed by local authorities. It was also emphasized that the demolition was not coordinated with Afghanistan’s Ministry of Information and Culture or the broader public, and the Afghan side expressed regret over the incident. Representatives of the interim government promised to properly commemorate Alisher Navoi, who is revered not only in Uzbekistan but also in Afghanistan, and pledged to construct a separate monument in his honor. Six months later, when the site was inspected, the area was fenced off with green fabric, but it remained unclear whether construction was underway. No clear information was provided about the nature of the planned complex. Uzbekistan’s Foreign Ministry stated that the construction of the monument had been agreed upon with the Afghan side and that the agreement remained in force, although the opening date was still unknown.

Following these events, Afghan statesman and former vice president of Uzbek origin, Marshal Abdul Rashid Dostum, along with his daughter Rohila Dostum, issued strong statements against the Taliban. They warned that the group would eventually regret its actions. Describing Alisher Navoi as a towering figure of intellect and culture, they condemned the destruction of his monuments as senseless and absurd and expressed deep regret.

“I received with pain and sorrow the news that the monument to Amir al-Kalam, Amir Alisher Navoi, a politician, scholar, and poet of Afghanistan and regional history, was destroyed in Mazar-i-Sharif. Such treatment of one of the founders of Mazar-i-Sharif and one of the greatest figures of Afghanistan and the world is an unbearable insult. I consider this an act of humiliation directed not only at the Afghan people but also at Uzbeks and Turkic peoples worldwide. This unforgivable act by the Taliban has deeply wounded my heart and the hearts of all admirers of Hazrat Navoi,” Dostum said.

Dostum’s daughter, former senator Rohila Dostum, also commented on the incident, describing the destruction of the Navoi monument as a symbol of the Taliban’s hostility toward cultural heritage and a sign of disrespect for the shared identity of Afghanistan’s peoples. She called on the international community to respond to the Taliban’s actions, labeling them an insult to great historical figures and a disregard for cultural, historical, and artistic values.

“The destruction of Amir Alisher Navoi’s monument by the Taliban is a disgraceful and anti-cultural act that demonstrates the group’s hostility toward the region’s historical and civilizational heritage. Such actions only intensify public resentment toward the Taliban. Cultural figures must condemn this act and take practical steps to protect humanity’s heritage,” she said.

In addition, in June 2025, many Uzbeks suspected of having links to Abdul Rashid Dostum were reportedly brought from Iran and executed. Dostum, who fled to Turkey in 2021, has since limited himself to issuing warnings against the Taliban. He called on the group controlling Afghanistan to leave the country, warning that otherwise the fate of up to 2,000 Taliban fighters killed in Dasht-i-Leili in December 2001 could be repeated.

“Let them not later ask us, ‘What happened in Dasht-i-Leili?’ Today, neither Trump, nor Putin, nor Afghanistan’s neighbors trust the Taliban. Let the people be certain: just as the Taliban came, so will they go. This is no joke,” he said.

It is known that in 2001, on the eve of the end of the Taliban’s first rule, a large group of its fighters was shot or suffocated in airtight metal containers near Shiberghan in Jowzjan province and buried in mass graves in Dasht-i-Leili. After returning to power in 2021, the Taliban built a wall around the mass graves and erected a mausoleum.

By November 2025, the Taliban launched another campaign against Uzbeks in the country. In Jowzjan, where Turkic peoples are most densely populated and Uzbeks make up more than half of the population, Uzbek-language inscriptions in Arabic script were removed from university buildings. The move sparked widespread protests, and after some time, Taliban officials were forced to reinstate the Uzbek language.

More recently, on January 2 of this year, Uzbek-language signage was removed from the facade of Samangan University, located in northern Afghanistan, where many Uzbeks live. About four days earlier, the Taliban had removed the old sign and reinstalled it without Uzbek.

Marshal Dostum described the removal of Uzbek from Samangan University’s signage as an open act of hostility toward the Uzbek language and culture, stating that no force could erase the language from the country’s cultural and social fabric.

Former Faryab governor Naqibullah Faiq described the incident as tribalism-driven and warned that such actions would fuel ethnic and linguistic hostility. Commenting on the former university signage, lecturer Muhibullah Muhib stated that after the institution received university status, the sign was changed by order of the Taliban’s Ministry of Higher Education. According to him, the proposal to include Uzbek was rejected based on an official letter from the ministry. The previous sign had been written in four languages: Pashto, Persian, Uzbek, and English.

For more than four years, the Taliban has repeatedly been accused of restricting the Uzbek and Turkmen languages and pressuring their speakers. During this period, Uzbek-language signs in government institutions were removed, and monuments and images dedicated to Turkic poets and writers were vandalized.

If such actions were taken against the Russian language, Russia’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova would “set the world on fire.” So what about Uzbekistan? Speaking to QALAMPIR.UZ, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Akhror Burkhanov emphasized that the situation in Afghanistan is being closely and continuously monitored, adding that any potential restrictions on the Uzbek language are a serious concern.

“Any possible restrictions on the use of the Uzbek language naturally cause concern for us. In this regard, regular dialogue is being maintained with the Afghan side on these issues,” he said.

According to Burkhanov, Afghan representatives stated that no restrictions have been imposed on the use of the Uzbek language and that no such measures are planned in the future. They also emphasized their deep respect for Uzbekistan, the Uzbek language, and the Uzbek people.

A few days later, on January 6, the Taliban informed representatives of Uzbekistan’s Foreign Ministry that no restrictions would be imposed on the Uzbek language in northern Afghanistan, including at Samangan University.

Afghan officials stated that there are no restrictions on the use of Uzbek and that signage at educational institutions is being standardized. They added that inscriptions at Samangan University would be displayed in Pashto, Dari, and Uzbek.

It was also announced that starting this year, a master’s program in Uzbek Language and Literature is planned to open at Jowzjan State University.

Today, the issue is not just about a single monument or a single sign. It is about preserving the memory, language, culture, and historical identity of an entire people. When a language disappears, a nation fades with it.

If such actions against the Uzbek language continue in Afghanistan, they will constitute repression not only against one ethnic group but against the historical and cultural balance of the entire region. Such policies have never brought stability and never will.

The Amu Darya may have separated peoples geographically, but no river, regime, or violence can sever history, language, and national memory. The question remains open: if others consider attacks on their language and culture a red line, why does ours remain merely an object of observation?

The full version of this material can be viewed in the video player above or on QALAMPIR.UZ’s YouTube channel.

Live

All