New Cold War: How the U.S.–China rivalry could benefit the world

Review

−

20 October 2025 6999 9 minutes

During the Cold War (1947–1991), the United States and the Soviet Union competed across two ideological blocs: capitalist and socialist. When the Cold War ended, the Soviet Union collapsed, but a new era of rivalry soon emerged between two major powers — the United States and China. U.S.–China relations began to warm in the early 1970s: in 1972, President Richard Nixon visited China, laying the groundwork to restore official relations after a 23-year hiatus. In 1979, Washington established full diplomatic relations with Beijing, recognizing the People's Republic of China as the sole legitimate representative of China, instead of the Republic of China in Taipei. Under Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms and the policy of openness, trade and investment between the two sides grew rapidly during the 1980s and 1990s. After China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, cooperation expanded even further. However, in the last decade, China’s swift rise and growing assertiveness — particularly in the South China Sea and around Taiwan — coupled with deepening trade tensions, have strained the relationship. Since the 2018 trade war, technological sanctions, and rising military friction, the U.S.–China competition has increasingly been described as a “new Cold War.”

Technological rivalry

Technology has become the sharpest arena of today’s competition. Artificial intelligence, semiconductors, 5G, mobile applications, and other advanced technologies form the core of this “second Cold War.” Western countries led by the United States dominate in advanced processors, modern manufacturing equipment, and software development. For instance, under the 2022 “CHIPS and Science Act,” the U.S. allocated $52 billion within a $525 billion initiative to strengthen microelectronics and AI industries. Simultaneously, Washington imposed export restrictions on several categories of advanced chips to China and banned key Chinese firms from accessing them.

These restrictions complicated China’s efforts to advance AI development. However, they also pushed Beijing to accelerate its “internal circulation” strategy, emphasizing domestic innovation. The country has developed its own AI projects, such as “HuggingGPT” and “DeepSeek.” Interestingly, training costs for these models are significantly lower than for OpenAI’s GPT-4 — about $5.56 million for DeepSeek V3 compared to $63 million for GPT-4.

The race for 5G dominance remains fierce. Huawei has become a global leader, serving as the main supplier of China’s mobile network infrastructure by 2024. Yet, since 2020, the U.S. and its close allies have labeled Huawei and ZTE as “security threats” and excluded them from 5G networks, even banning their participation in network construction.

In response, China restricted the use of Apple products — particularly iPhones — in government agencies and state-owned enterprises. The ban reportedly covers about 150,000 large state companies and nearly 56 million employees.

China is one of Apple’s most important markets. In 2022, roughly 19 percent (about $75 billion) of Apple’s $394 billion global revenue came from China and Hong Kong. Therefore, these restrictions dealt a serious financial blow to the company.

The case of TikTok represents another front in the tech battle. The Chinese-owned global short-video platform is viewed in the U.S. as a security risk. In 2024, Congress passed a law requiring ByteDance to sell TikTok or face a ban by January 19, 2025. Surveys show that 75 percent of Americans are concerned about TikTok’s Chinese ownership, while 34 percent support a complete ban.

In conclusion, the United States is trying to maintain its global technological dominance through export controls, domestic innovation funding, and alliances with partners. Its advantages lie in research infrastructure, a large market, top-tier universities, and industry giants like Apple, Nvidia, and Google. However, the country faces challenges in rebuilding microchip production lost since the 1990s — creating a fully domestic supply chain could cost around $1 trillion — and in its dependency on Asian suppliers for raw materials and components. China, on the other hand, is investing heavily in AI and chip production at the state level. In 2023, the revenue of China’s semiconductor industry reached $179.5 billion, and the country aims to achieve 50 percent self-sufficiency by 2025. Its strengths include a vast domestic market of 1.4 billion people, experience in technology transfer through global partnerships, and major tech players such as Huawei, Alibaba, and Tencent. Yet China remains reliant on foreign technology, particularly advanced microchip tools like ASML’s EUV lithography systems. In early 2023, its imports of high-tech equipment rose 93 percent to $8.75 billion, underscoring a key strategic vulnerability.

Economic policy

In 2018, then-President Donald Trump launched a large-scale trade war against China, raising tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of Chinese goods. For example, under the “Phase 1” agreement of 2020, the U.S. imposed an average tariff of 19.3 percent on 66.6 percent of Chinese imports, covering roughly $335 billion in goods. Beijing retaliated with an average tariff of 21 percent on U.S. imports. According to Trump, these measures were a response to China’s “unfair” industrial policies. However, many economists warned that such tactics could raise prices and disrupt markets.

During Joe Biden’s presidency (2021–2024), most of the Trump-era tariffs remained in place. Biden introduced additional tariffs on strategic sectors, including electric vehicles, batteries, solar panels, and semiconductors. In spring 2024, his administration announced plans to raise tariffs on Chinese cars and tech products, extending them even to previously exempt goods such as televisions and medical devices. At the same time, Biden sought to strengthen supply chain security through initiatives like the CHIPS Act and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). The administration also tightened screening of foreign investments via CFIUS to limit access to strategic sectors.

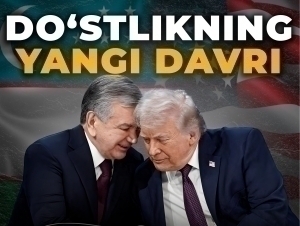

Under Trump’s second term, relations escalated further. In early 2025, he imposed an additional 10 percent tariff on all Chinese imports, later threatening to raise rates to as high as 125 percent in certain sectors. In May, however, negotiations in Geneva resulted in a temporary agreement to cap tariff increases at 10 percent. The situation soon worsened again: in October 2025, after China imposed export controls on 12 of its 17 rare earth elements, Trump announced a 100 percent tariff on imports. Analysts at CFP noted that Trump effectively threatened China with tariffs up to 145 percent, prompting Beijing to respond with duties as high as 125 percent on U.S. goods.

China’s reaction was equally sharp. It restricted the export of rare metals vital for high-tech industries, calling it a response to U.S. restrictions against its firms. Beijing focused on diversifying its economy, boosting domestic demand, and expanding trade with partners in Europe and Asia. Meanwhile, many major technology companies began relocating production from China to countries like Vietnam in response to global supply chain risks. Amid geopolitical turbulence, supply chains are being reshaped by new policies and investment flows. Overall, between 2021 and 2025, Washington maintained and even intensified Trump’s tariff policies, pushing trade tensions with China to new heights.

Political relations

President Nixon’s visit to Beijing in February 1972 marked a major turning point. During the visit, the “Shanghai Communiqué” was signed, establishing the foundation for the “One China” policy and signaling a commitment to peaceful resolution of the Taiwan issue. According to the communiqué, the U.S. acknowledged Beijing’s position that there is only one China and that Taiwan is part of it. In December 1978, Washington officially recognized the People’s Republic of China as the sole legitimate government of China and established formal diplomatic relations starting January 1, 1979. As a result, official ties with Taiwan ended, but the U.S. Congress passed the “Taiwan Relations Act,” committing the U.S. to provide Taiwan with defensive weapons.

Since then, the One China principle has remained central to U.S. policy. Washington recognizes the People’s Republic of China as the sole legal government while maintaining unofficial commercial and defense ties with Taiwan. Beijing, however, regards Taiwan as a breakaway province that must eventually be reunified — by force if necessary. This difference has repeatedly surfaced in bilateral talks. For example, in 2010, when Secretary of State Hillary Clinton reaffirmed freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, China viewed it as interference in its internal affairs. The Taiwan issue continues to be a major source of contention.

China’s 2001 accession to the World Trade Organization significantly boosted its global economic role. In 1999, trade between the U.S. and China totaled less than $100 billion; by 2019, it had reached $558 billion. Over the same period, China’s economy grew more than elevenfold and became the world’s largest exporter by 2009. Over the last two decades, China has reemerged as a leading global economy and sought a more prominent role in international institutions such as the World Bank, G20, and the United Nations. The 2008 Beijing Olympics and 2010 Shanghai Expo symbolized this resurgence.

During the 2010s, competition intensified once again. Under President Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” strategy, the U.S. declared freedom of navigation in the South China Sea a “national interest.” Meanwhile, China expanded its global diplomacy, joining the Paris Climate Agreement and investing heavily across Africa, Central Asia, and Latin America. The U.S., aiming to retain influence in the region, launched the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2011, notably excluding China from its initial membership. Consequently, competition spread across bilateral, regional, and global levels, with disputes over the South China Sea becoming a persistent flashpoint.

Analysts predict that in the coming years, U.S.–China rivalry will grow even more complex and intense. Strategic and economic confrontations may deepen, particularly around Taiwan or in the South China Sea, posing risks to global stability. Yet, this rivalry could also generate benefits — driving innovation, diversifying investments, and establishing more resilient global frameworks. Experts suggest that under the label of a “new Cold War,” relations between Washington and Beijing may oscillate between confrontation and dialogue, encouraging the creation of new mechanisms and rules for coexistence. What matters most is that both powers continue to seek solutions to global challenges while respecting international norms.

Bekzod Polatov

Live

All